Canada, South Korea and the New Geometry of Defence

%4010x.png)

Digital Marketing & Communications Specialist

Samuel Associates Inc.

For most of the post–Cold War era, Canada’s defence relationships were easy to describe and easier to draw. Thick lines ran south to Washington, east across the Atlantic, and outward through multilateral institutions that promised stability through permanence. Alliances were assumed to be enduring; supply chains were presumed reliable; geography was treated as a strategic asset rather than a vulnerability.

That world is ending.

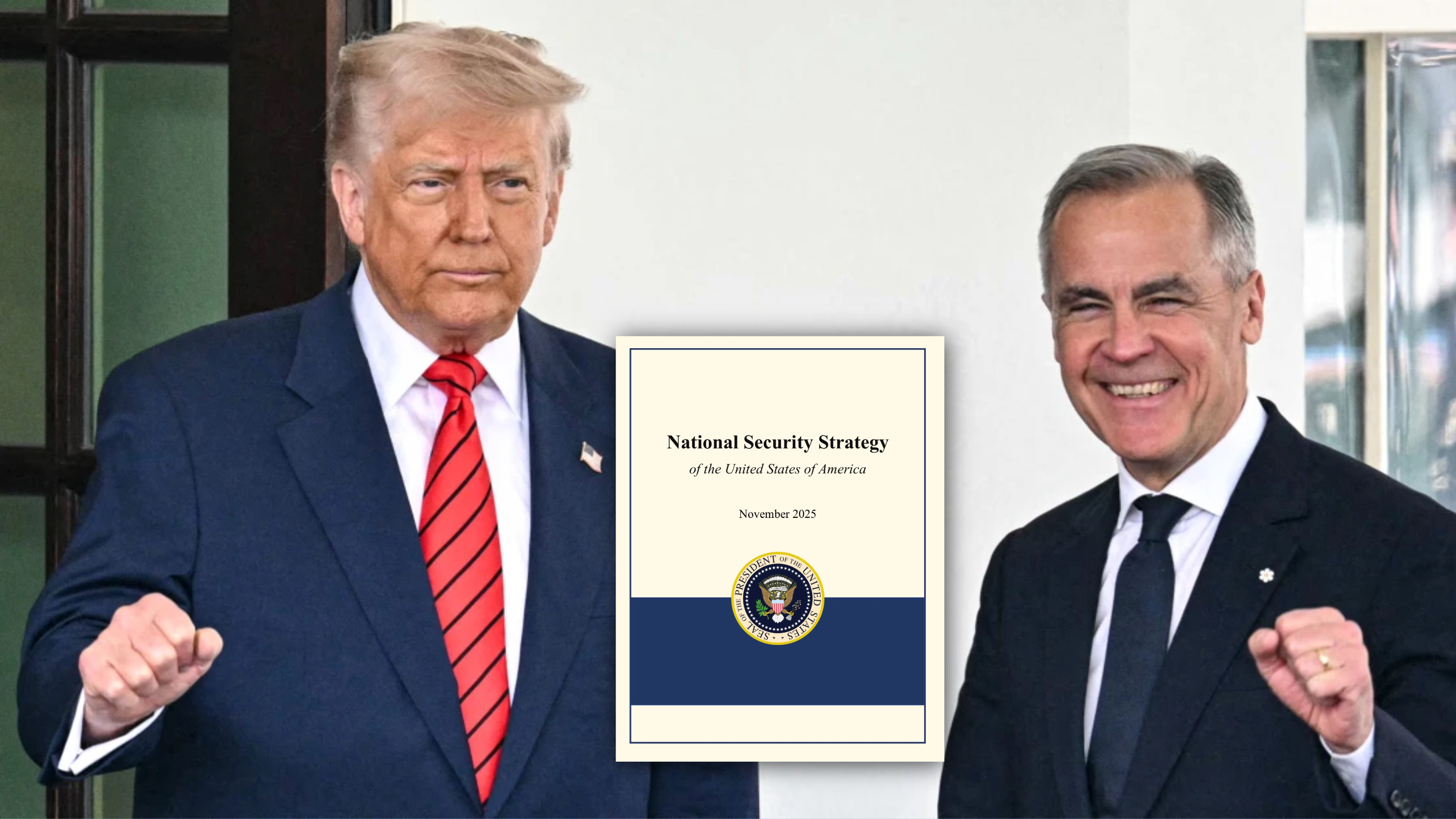

What is emerging in its place is not chaos, but geometry—variable, adaptive, and increasingly purpose-built. Prime Minister Mark Carney has spoken of this moment as one requiring diversification and variable geometry: partnerships formed around capability, relevance, and shared risk rather than legacy alone.

Few relationships illustrate this transition more clearly than Canada’s evolving defence partnership with South Korea.

From Alignment to Architecture

Canada and South Korea are frequently described as like-minded democracies. The phrase is accurate, but it understates the strategic logic now driving their cooperation.

South Korea exists in a state of permanent strategic awareness. Its defence posture is shaped by proximity to adversaries, rapid technological cycles, and the necessity of maintaining both readiness and industrial scale. Canada, by contrast, has long benefited from geographic distance and alliance structures that softened urgency.

That insulation is eroding.

The Arctic is no longer remote. The Indo-Pacific is no longer peripheral. Defence supply chains are no longer guaranteed. As Canada adapts to this reality, its partnerships are shifting from inherited alignments to constructed architectures—designed for specific threats, domains, and time horizons.

This is the practical meaning of variable geometry.

Submarines and Strategic Depth

Canada’s pursuit of a new submarine fleet is often framed as a procurement challenge. It is more accurately understood as a strategic inflection point.

Submarines are not merely naval platforms; they are instruments of deterrence, sovereignty, and intelligence. For Canada, they represent one of the few capabilities that can operate discreetly across the Atlantic, Pacific, and Arctic while reinforcing both national autonomy and alliance commitments.

South Korea’s submarine industrial base reflects decades of sustained investment driven by existential necessity. Its platforms are designed for contested environments, high survivability, and integration with allied command structures.

From a Samuel Associates perspective, the relevance of South Korea to Canada’s submarine ambitions lies not only in design or cost, but in strategic congruence: an industrial partner shaped by pressure, scale, and speed.

Such a partnership would not displace traditional allies. It would add depth—diversifying supply chains, strengthening deterrence, and embedding Canada within a broader, more resilient defence industrial ecosystem.

NORAD, Technology, and Continental Resilience

Canada’s commitment to NORAD modernization reflects a deeper shift in how continental defence is understood.

The challenge is no longer limited to aircraft crossing airspace. It now includes hypersonic weapons, space-based surveillance, cyber disruption, and sensor saturation across vast northern approaches. Geography, once Canada’s shield, has become an exposure.

South Korea’s strengths in advanced sensors, AI-enabled defence systems, and rapid manufacturing offer meaningful complementarities. While NORAD remains a bilateral command, its effectiveness increasingly depends on a wider constellation of trusted technologies and industrial contributors.

Variable geometry does not weaken core alliances. It reinforces them by broadening the base of innovation and resilience on which they depend.

The Arctic as a Strategic Connector

The Arctic is often described as Canada’s backyard. In strategic terms, it is rapidly becoming a shared frontier.

Climate change, new maritime routes, and great-power competition are transforming the Arctic into a zone of heightened strategic interest. Canada’s response requires under-ice capabilities, persistent surveillance, and logistics suited to extreme conditions.

South Korea—an Indo-Pacific maritime power with global trade dependencies—has a clear interest in Arctic stability and access. Cooperation need not be comprehensive to be consequential. Targeted collaboration in ship design, cold-weather systems, and sensing technologies fits naturally within a variable geometry framework.

Partnerships form where interests intersect, and evolve as those intersections shift.

Industrial Capacity as Strategic Power

Perhaps the most consequential dimension of Canada–South Korea cooperation lies beyond platforms and theatres: the defence industrial base itself.

In an era of geopolitical fragmentation, industrial capacity has become a strategic asset. Nations able to design, produce, and sustain advanced systems at scale possess a form of power that cannot be improvised in crisis.

South Korea has demonstrated an ability to move from domestic requirements to global defence production with speed and reliability. Canada, meanwhile, is reassessing how sovereignty, resilience, and economic security intersect in defence policy—particularly as it prepares a renewed Defence Industrial Strategy aligned with the Prime Minister’s diversification agenda.

A deeper industrial relationship—through co-production, technology sharing, and joint innovation—would support Canada’s transition from a primarily consuming defence market to a more participatory one.

A Partnership Suited to the Moment

What is emerging between Canada and South Korea is not a traditional alliance defined by permanence and exclusivity. It is a partnership defined by relevance.

It reflects a broader Canadian recognition that security in the 21st century will be assembled, not inherited. It will be built across domains, regions, and industries, with partners selected for what they contribute to the overall structure rather than where they sit in legacy hierarchies.

This is variable geometry translated into practice.

For Canada, the opportunity is clear. By engaging partners like South Korea—capable, democratic, industrially advanced—Ottawa can strengthen deterrence, diversify risk, and reinforce its place within a more complex but more resilient global security architecture.

The map is changing. The structure is taking shape. And the geometry, at last, is deliberate.

%4010x.png)

%4010x.png)